The rare blood-clotting reaction that has disrupted the rollout of the Oxford/AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson coronavirus vaccines is now the focus of a heated scientific debate over why the shots may be triggering the response and how to stop it.

The reaction, which has been named vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VIITT) by some scientists, has been recorded in approximately 300 of the 33.6m people who have received the AstraZeneca vaccine in Europe and at least eight of the 7.4m recipients of the J&J shot in the US.

In response, use of the AstraZeneca jab has been restricted or suspended in more than a dozen countries, while the US has paused use of the J&J vaccine and the company has delayed its rollout in the EU.

If scientists are able to identify a mechanism that links the vaccines to the extremely rare, often fatal, condition, they say drug manufacturers may be able to adapt their formulas to prevent it happening altogether.

“When you know the mechanism, you know how to prevent it,” said Johannes Oldenburg, professor of transfusion medicine at the University of Bonn, who chairs a team investigating the problem and potential treatments.

But for now the scientific community is divided, with some speculating that the response could be caused by the adenoviral vector in the two vaccines, and others, including University of Oxford scientists who worked on the AstraZenca shot, arguing there is no evidence to support this.

One group of scientists from laboratories in Germany and Austria, led by clotting expert Andreas Greinacher, said in March that the unusual constellation of symptoms resembled a rare reaction to the blood-thinning drug heparin, called heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT).

HIT occurs in about four out of every 1m people who receive the drug, causing the body to produce antibodies against a protein called platelet factor 4 (PF4). This causes the blood to form huge clots in unexpected places, such as the brain and abdomen, using up the body’s scarce platelet supply.

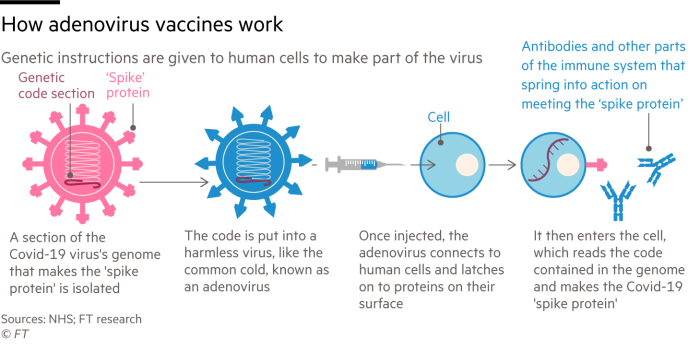

The AstraZeneca and J&J shots are both adenoviral vector vaccines — as are Russia’s Sputnik V jab and the shot developed by China’s CanSino Biologics — meaning they use an adenovirus, such as the common cold, to deliver the vaccine protein into the body.

Each of the four vaccines uses a slightly different adenovirus, but in each case scientists remove any genetic material that would enable it to spread or cause disease. That material is then replaced with genetic instructions to replicate the spike protein on the surface of the Sars-Cov-2 virus and trick the body into thinking it has been infected with Covid-19.

Currently, a leading hypothesis among scientists is that it is actually the adenoviruses in the two different vaccines that are triggering an exaggerated immune response in a very small number of people, generating antibodies that target PF4 blood platelets.

Hildegund Ertl, a researcher who works on adenovirus vaccines at The Wistar Institute in Philadelphia, said the reaction following both J&J and AstraZeneca vaccines appeared to be very similar, which “raises concern that the adenovirus is causing this”.

AstraZeneca said it was “working to understand the individual cases, epidemiology and possible mechanisms that could explain these extremely rare events”. J&J did not immediately respond.

Sue Pavord, chair of the Expert Haematology Panel in the UK, noted that the chimpanzee adenovirus used in the AstraZeneca shot did not usually infect humans but said that part of the genetic material in the vaccine could potentially trigger this rare immune response through a process known as “sequence homology”.

There may be, she said, some genetic connection between heparin and the DNA or protein sequences contained in the adenovirus, which is causing an almost identical antibody response in some patients. “This looks very much like HIT without heparin. It’s the same mechanism,” she said.

Pavord and other scientists have also been working on treatments for those that display VIITT, which has so far killed one in five people that have reported the symptoms in the UK. The most successful involves regular infusions of something called gamma globulin — a protein fraction of blood plasma that contains helpful antibodies — and has already halved the fatality rate.

John Bell, regius chair of medicine at Oxford who has overseen the vaccine partnership between the university and AstraZeneca, argued that the HIT-hypothesis lacked any firm evidence, however.

“They’ve tried to fit this syndrome into a HIT, but no one has been able to explain exactly how that works,” said Bell. “I think the answer is that no one knows, including the haematologists.”

Scientists at Oxford have had the blood sera of 500 individuals from their vaccine trials analysed and found that none of them contained PF4 antibodies, according to people with knowledge of the investigation.

Rather than a reaction to the adenoviral vector, Bell thought the blood disorder was more likely to be a response to the spike protein in the vaccine.

Proponents of this hypothesis highlight that Sars-Cov-2 causes more severe clotting problems, and much more commonly, than any of the current Covid-19 vaccines. Researchers at Oxford recently found that blood clots occurred in about 39 in 1m coronavirus patients.

“This is a feature of the disease, which means it’s induced by the virus, or a bit of the virus,” Bell said. “Some vaccines may produce more spike than others. I think that’s something we have to entertain.”

Adenoviral vector vaccines have been under development since the 1980s and widely trialled but until Covid-19 the technology had been used in only one commercially available inoculation: a rabies vaccine used to immunise wild animals.

Other scientists also said it was too soon to blame the adenoviral vector, particularly as no definitive causal link has yet been established between the blood disorder and either of the vaccines.

“It could be a contaminant, or the preservatives, or the stabilisers,” said Gary Nabel, who discovered the first Ebola vaccine and was chief scientific officer at Sanofi until late last year. “If it’s one of those, you could get rid of it and potentially make [the vaccine] safe.”

Article From & Read More ( Covid vaccines and the race to understand blood clots - Financial Times )https://ift.tt/32wY8FO

Health

No comments:

Post a Comment