Not long ago, Joe Montminy was a hard-charging market research executive, wowing audiences at conferences all over the world. "I loved the job," he said.

Correspondent Susan Spencer asked, "You were good at this job?"

"I'd like to think I did a good job at it, yes."

But gradually he felt that the job he'd mastered was somehow mastering him: "There was one situation that really stands out. We were on a call going through a number of topics, and I had a hard time following the conversation and connecting the points. And that had never, ever happened to me before. And that's when I knew something wasn't right, because It was now affecting my ability to do my job."

So, in 2017 Joe saw a neurologist, whose diagnosis stunned him: Early onset-Alzheimer's. He was 54.

Spencer asked, "What did the neurologist tell you the outlook was?"

Montminy replied, "She actually said, you know, 'Joe, over the next three to five years you are gonna start to experience some declines. And then, you're likely not going to recognize your family in five to seven years,' and that I had a life expectancy of around ten years."

His reaction was one of shock. Just a month later, he retired from the job he loved. Today, he makes the most of family time at home in Plymouth, Mass.

But he's haunted by what lies ahead. "I've had friends say, 'Oh, you've caught it early. Hopefully, they can help you and you'll get better.' People don't realize that with Alzheimer's, there is no cure. It can be a fatal disease."

Dr. Daniel Gibbs, a neurologist in Portland, Oregon for nearly 25 years, told Spencer, "Alzheimer's Disease is the most common form of dementia. The key is, it's a progressive loss of brain function."

And an astounding six million Americans suffer from it, says Gibbs.

Spencer asked, "As a physician, what was the most difficult aspect of treating Alzheimer's patients?"

"I just felt so hopeless," Gibbs replied, "and it was hard for me to give any hope to the patients. Because we all knew what was in store."

"The cause of Alzheimer's Disease, broadly speaking, is really a challenge still today," said Maria Carrillo, Ph.D., chief science officer at the Alzheimer's Association in Chicago … a challenge that so far has evaded answers.

But Carrillo is nonetheless optimistic: "We have hope on the horizon, and that hope is that there are new treatments, not only available today, but hopefully in the near future."

One approach goes after the abnormal deposit of protein found in the brains of Alzheimer's patients. They're called amyloid plaques, and they may show up decades before symptoms do.

Spencer asked, "So, it's possible that, in the future, we'll be treating it before it's even symptomatic?"

"That is really the goal," Carillo said, "to be able to stop this disease in its tracks, to stop it at the biological timepoint when proteins are starting to accumulate in the brain that ultimately will lead to those memory and behavior changes that today we know of as dementia."

That's the thinking behind Aduhelm, the first new FDA-approved Alzheimer's drug in almost two decades.

When asked why new medications for Alzheimer's are so few and far between, Gibbs replied, "Well, it's not for want of trying. It's a very complicated disease, is the short answer."

The excitement over Aduhelm stemmed from its proven ability to clear those protein formations, the amyloid plaques.

When asked if he would take the drug if offered, Joe Montminy said, "If I was eligible and if I had the insurance coverage, I would absolutely take the drug. My challenge is the price tag. I cannot afford the $56,000 price tag."

And for now, insurance coverage is no guarantee, though drug maker Biogen says it does offer "programs to help patients … assess eligibility for financial assistance ..."

But beyond the staggering cost is a more urgent concern: does Aduhelm really do anything to stop symptoms?

Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, professor of medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, said, "The new drug that the FDA approved in June targets amyloid plaques very effectively. But unfortunately, the drug doesn't seem to have any clear effect on the progression of Alzheimer's Disease."

Kesselheim was on the FDA Advisory Panel on Aduhelm, until he quit in protest when the agency gave the drug a green light … a move he calls "probably the worst drug approval decision in recent U.S. history."

Spencer asked, "How can you say definitively that it doesn't work any more than the FDA could say definitively that it does?"

"You can't say definitively that it doesn't work; you can't say definitely that it does work, either," said Kesselheim. "And in that circumstance, you need to do some more testing of the drug. The system in our country is that in order for a drug to be approved by the FDA, it has to show substantial evidence that the drug actually does work. And in this case, there isn't good evidence that the drug works."

But the FDA made Aduhelm available while studies continue, citing the "unmet needs for patients [facing this] fatal disease," and concluding, " … it is reasonably likely that … reduction in amyloid plaque will result in meaningful clinical benefit …"

"Reasonably likely" sounds pretty good to patients like Joe Montminy: "It's a major, major breakthrough that has taken us from drugs that only deal with the symptoms, to a drug that now can deal with one of the root causes of the disease."

"Possibly?" said Spencer.

"Possibly."

Spencer asked, Gibbs, "Describe for me the pressure from patients and their families to find a cure."

"There is pressure," he said. "The experience that we have with Alzheimer's Disease, most of us, is when we, a relative or an acquaintance is in the nursing home and dwindling away, doesn't recognize anybody, and it's just, you know, a terribly frightening thing to think, 'That's my future.' And it is devastating."

A devastating future Dr. Gibbs now sees through a very different lens. He no longer practices medicine, he said, because he has Alzheimer's. "And even though I'm still in the mild cognitive impairment stage of it, I stopped practicing neurology."

"Do you think that, being an expert in this field, does that at this point make it harder or easier for you to deal with it?"

"I mean, I know what to expect," Gibbs replied, "but I also know what I need to do to hold off the bad stuff at the end as long as possible."

Gibbs enrolled in an early trial of Aduhelm, which landed him in the ICU. He is one of a small number of patients who suffered serious side effects. "My severe reaction doesn't affect my opinion on the FDA's approval," he said. "Because they're rare. And I fully recovered."

He said he is still optimistic about this class of drugs.

And as for Joe Montminy, he told Spencer, "I've really come to realize how precious time is. So, I'm much more focused on how I spend my time and who I spend it with."

He said he'd consider any new medication, controversy or not. "If you don't take chances, nothing good happens," Montminy said.

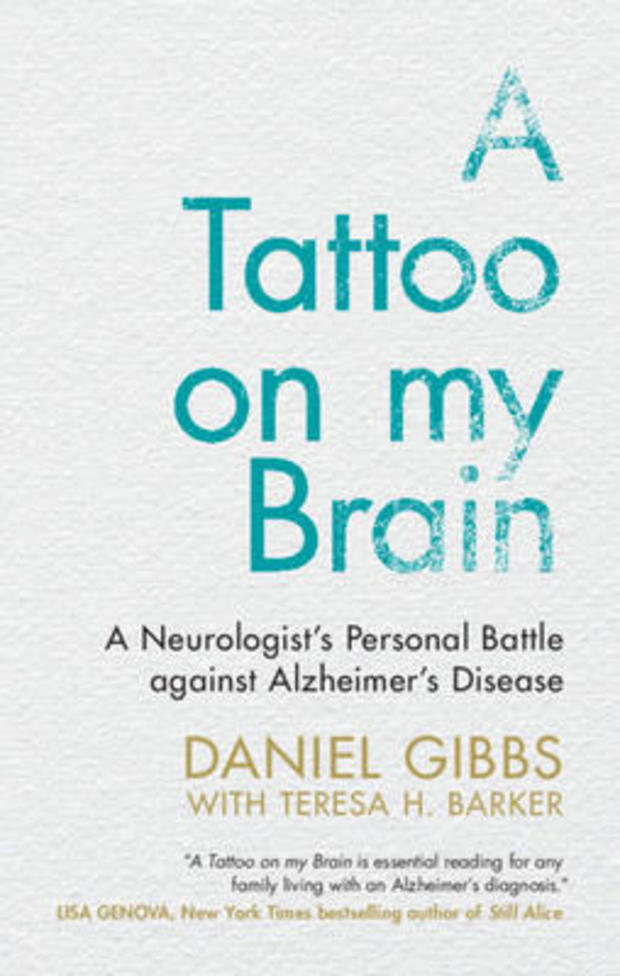

READ A BOOK EXCERPT: "A Tattoo On My Brain: A Neurologist's Personal Battle Against Alzheimer's Disease" by Dr. Daniel Gibbs

For more info:

Story produced by Amiel Weisfogel. Editor: Carol Ross.

See also:

Download our Free App

For Breaking News & Analysis Download the Free CBS News app

https://ift.tt/31abquL

Health

No comments:

Post a Comment